https://www.lifegate.it/ghiacciai-italiani-alpi-2024

- |

“After the great drought, record glaciers. Never so abundant for twenty years”.This is how some Italian newspapers headlined at the beginning of July after the Harp measurements (Regional Agency for Environmental Protection) of Valle d'Aosta, Piedmont and Lombardy have reported abundant snow accumulations on the glaciers of the Italian Alps in the spring 2024 season.But, contrary to those headlines, we can't say that the glaciers are fine now.

Snow accumulations on the Italian glaciers of the Alps

The last few months, in particular late winter and early spring, have been rich in rainfall which lasted until late May, allowing the snow cover to remain even at the beginning of summer. We are therefore talking about an abundance of snow, not ice.

For example, the data collected by Arpa Valle d'Aosta with the Diati department of the Polytechnic of Turin, show that the snow accumulations (measured in water accumulation in the snow) on Rutor glacier, in the La Thuile Valley, are the second highest in the last twenty years, slightly lower than the 2013 record.Even those collected by Arpa with the Gran Paradiso National Park on Timorion glacier show that thesnow accumulation this year exceeded the last record recorded in 2013 by 30 percent, and was three times higher compared to that recorded in the winter of 2022-2023.

The years 2022 and 2023 were in fact characterized by long periods without precipitation in the Alps and by temperatures well above the average with freezing temperatures at altitudes never reached, which contributed to worsening the drought which had already persisted even since the winter months and to accelerating the melting of ice.This year's data relating to snow accumulations are therefore positive, and they also give us breathing space in terms of water resources, because they are reserves that have the capacity for gradual release. But we must consider the broader picture in which they fit:we cannot judge the progress and well-being of a glacier from a single season.

One snowfall does not make a glacier

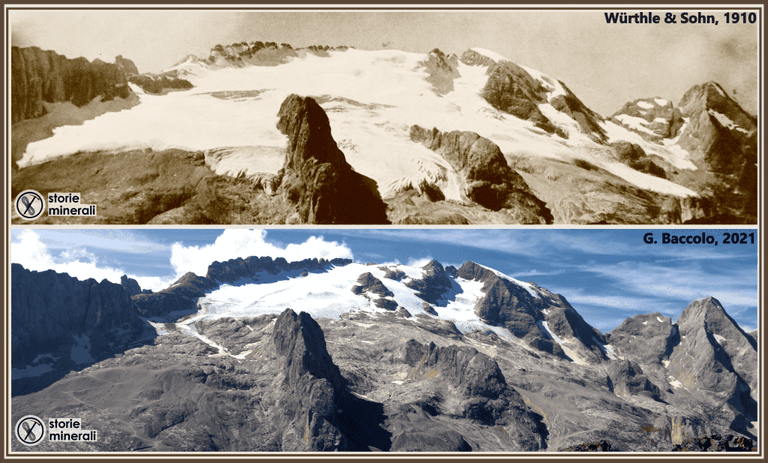

“We must make a distinction betweeninstant image of today and an image that instead considers a longer time interval, a trend", he begins to explain to us Giovanni Baccolo, researcher at Roma Tre University on glaciers, environment and climate and member of the Italian Glaciological Committee, with whom we spoke about the issue.“The instant image shows us that a part of the Alpine glaciers is still covered in snow, now in late July.Last year, however, the ice was uncovered and began to melt as early as the end of May.So things are definitely better."

This year, in fact, the ice remained covered by snow and, by not receiving direct sunlight, the moment of the season in which it begins to melt was delayed.“In a certain sense, the snow that accumulates sacrifices itself in place of the ice:it is this that should melt first, the ice must only do so at the end of the season.So this year is certainly positive,” continues Baccolo.“But if we put this snapshot in an album of photographs showing the progress of the glaciers in recent decades we certainly cannot say that things are going well, or that this season in terms of snow accumulations may have somehow solved the problem of retreat of glaciers, because a single season is not able to influence the behavior of a glacier, it takes many years in a row to generate a response."

How a glacier works

The behavior of a glacier, In fact, it develops over a long period of time.To understand the role of snowfall, like the one in the snapshot we just took, in relation to the glacier, we need to take a step back and understand how the latter works.“To be defined as such, a glacier must produce new ice every year”, Giovanni Baccolo explains to us.“This means that it must be able to conserve at least a minimum quantity of the snow that accumulates on the surface in winter, which creates new ice year after year.If we observe a glacier at the end of summer and we don't see snow, but dirty, black ice, it means that the glacier can no longer produce new ice, it is therefore a fossil.The fundamental thing is therefore the presence of snow at the end of summer, which generates the production of new ice, and which in turn automatically begins a flow:the new ice produced at altitude must be transported downstream, with a downward movement.However, if new ice is no longer produced, the flow slows down, until it becomes still.At that point it can no longer even be defined as a glacier because a plate of ice without dynamics is defined as a glacier snow”.

How are the Italian glaciers doing?

How important the global context is, and not just the local one, makes us understand yet again record we recorded in June 2024:it was the warmest June ever, it is the thirteenth consecutive month of record temperatures, and the twelfth in a row with a temperature increase of over 1.5 degrees centigrade compared to pre-industrial levels.THE Italian glaciers they fit precisely into this context.Indeed, as Baccolo reminds us:“The Alps are not only following the trend of rising temperatures, they are also exceeding it. They warm more than the planet's average, with an increase of 2 degrees in temperature compared to the pre-industrial period, while the global average is 1.5.Furthermore, the lower glaciers today have not yet had time to reach equilibrium with the climate.That's why I call them climate fossils:they move only by inertia, but from a climatic and glaciological point of view they should have disappeared, because they no longer know how to make new ice".

It is no coincidence that the Alps, like Europe as a whole, are considered hotspot for i climate changes, i.e. areas particularly sensitive to their effects.And the last two years have been a demonstration.“They were the worst ever since we started measuring,” continues Baccolo.“The mass loss of the glaciers was enormous, the most negative balance ever, so much so that scientists had to update the graph axes to accommodate these two years.In the Swiss Alps between 2022 and 2023, 10 percent of all the ice was lost, and this data makes us understand what also happened in the other Alpine sectors, including those of the Italian glaciers".

“If I have to think about the future, I think of the summer of 2022, that of the collapse of the Marmolada, which was very violent from a climatic point of view for the Alps,” says Baccolo.“Thermal zero above 4,000 metres, in some events above 5,000 metres:practically in those days all the ice present in the Alps was melting, as on the top of Mont Blanc.In certain terms that summer can anticipate the typical summers we can expect in the coming decades”.Following this trend, in fact, all glaciers below 3,500 meters are destined to disappear by the end of the century.

For glaciers, all is not lost

What we know, however, is that something can still be done.Indeed, one thing is clear: reduce emissions.In fact, the models say that by the end of the century, depending on how much we manage to reduce emissions, we could have different scenarios.If we manage to respect theParis Agreement, limiting the increase in global average temperature to within 1.5 degrees, between 30 and 40 percent of the ice that was there in 2015 will survive by the end of the century.“The only solution is to reduce emissions,” confirms Baccolo.“In this way we saw that we would save a significant portion of the ice in the Alps.Maybe it doesn't seem like much, but in reality there are other areas of the planet where the Paris Agreement would allow an even greater quantity of ice to be saved.We cannot expect the glaciers to return to the conditions they existed a few decades ago, but we should absolutely try to limit the damage and science tells us that it is not too late to do so, even though the time available is becoming increasingly shorter."

Precisely for this reason, correct information and dissemination on the situation of the glaciers and, above all, on the broader picture of the climate situation is essential.A balance that is not taken for granted, but essential so that we focus on the actions necessary to combat the effects of climate change, without exaggerating in alarmism and without falling into simplifications.“I believe that glaciers have played an important part in helping people learn about these issues and above all to see with their own eyes the effects of climate change:the retreat of glaciers and their disappearance is aone of the most powerful images”, concludes Baccolo.“But we must also try to give ideas on the possibilities we have, whetheradaptation or mitigation, the two ways we have to limit the damage of climate change.We must tell what is happening but also push for disclosure of what we can do for ensure the least possible damage to both natural systems and our civilizations”.

Glaciers around the world, not just in the Alps, contain more than 60 percent of all the fresh water on our planet.Entire communities, habitats, ecosystems, and part of our future depend on them.Knowing them and knowing their state of health gives us more awareness to preserve at least part of these immense masses of ice that contain stories of a time that is difficult to imagine.It is no coincidence that we perceive a feeling of helplessness when we find ourselves in their presence.A sensation that we must continue to perceive in front of their majesty.

Glaciers are a different world than everyday life.The rules and processes that happen here are unique, it's like entering another planet temporarily, but within reach.I am a sliver of a different world that was trapped on Earth.