https://www.valigiablu.it/consenso-scienza-cosa-dice-cambiamento-climatico/

- |

Climate denialism is a phenomenon documented by dozens of books, studies and journalistic investigations.It is a real, historical and phenomenon organized.Whatever the reasons that push us to embrace it - personal beliefs, economic interest, political ideology or a combination of these elements - denialism is based on the production and diffusion of misinformation.This misinformation also manages to reach public opinion through the voices of those who we can define as "false experts", or "pseudo-experts".

We have also seen this in recent weeks:people appear in the media who talk about climate change with the hat of experts, even when they have no actual expertise on the subject.Recently he intervened on La7 Franco Prodi, an atmospheric physicist who has not worked on climate change during his career.These people give interviews, organize conferences, circulate petitions.In almost all cases they have never published anything relevant regarding climate change in peer-reviewed scientific journals.Their theses clash with what the scientific community says.

Denialism exploits different techniques and arguments.But there is one constant in his modus operandi:target scientific consensus and its own legitimacy.The presence of pseudo-experts in the media, who address the public directly, gives the misleading impression that the scientific debate is still open.

Scientific consensus is a central feature of modern science.Since the 19th century, science has increasingly become a collective enterprise, involving thousands of scientists globally.In this community work of building knowledge, some make a more important contribution than others and their name is associated with a significant stage in the history of a discipline.

Some research has shown that scientific consensus acts as a gateway belief, that is, as a sort of cognitive gate through which the formation of opinions passes. Correctly communicate the position of science on climate change improves understanding of the topic.In order not to be fooled by misinformation and to understand how science works and advances along the tortuous road of knowledge, it is therefore essential to become familiar with the concept of scientific consensus.

First of all, we should not think of this consensus as a formal decision that scientists make at a precise moment, perhaps with a majority vote.Its formation is the result of a spontaneous process, which occurs thanks to a choral work of accumulation of evidence and knowledge.Once a consensus has emerged, scientists can acknowledge its existence, through personal statements and the positions expressed by scientific societies and organizations.Can we measure scientific consensus with any accuracy?Yes, it's possible.This is what has been done on climate change.

In a study published in 2004 in the journal Science, science historian Naomi Oreskes collected summaries of 928 scientific articles published between 1993 and 2003.None of these rejected the position that there is global warming caused by human activities.75% agreed with this position and 25% did not comment.In 2013 John Cook and other authors they analyzed The abstract of 11944 articles published between 1991 and 2011.Of the articles that stated the position on anthropogenic warming, 97.1% acknowledged its existence.Additionally, the authors invited scientists to evaluate their own papers.Of those who responded, 97.2% stated that they supported this position.

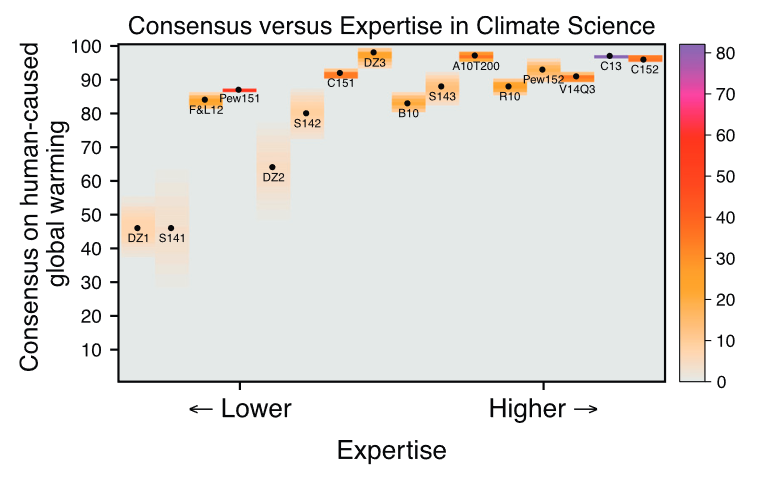

A item published in 2016 presented a summary of the studies carried out from 1991 to 2015:twelve published studies and two surveys conducted by two organizations.The authors' conclusion was that scientific consensus on climate change can be placed around 97%.The authors noted that, depending on the methodology, consensus ranged between 90% and 100%.The discrepancy between percentages resulted, primarily, from differences in expert database selection;from the exact definition of the position on which to evaluate consensus;by differences in the treatment of responses that did not overtly express a position.An important aspect was that concerning the specific competence of the scientists.“The greater the climate experience of the scientists examined, the greater the consensus on human-caused global warming,” the authors write.

Two new research were published in 2021.That of Mark Lynas and colleagues applied the methodology of the 2013 study to a database of articles published between 2012 and 2020, finding a consensus percentage of around 99.6%.If we consider that the articles evaluated were published in more recent years than those included in the 2013 study, the fact that the percentage is growing, even if it already gives a very high value, is consistent with a consensus that is strengthening over time .Within a database of 88,125 publications, Lynas and colleagues found 28 articles who they were able to classify as “skeptics”.The name of appears among the authors of five of these articles Nicola Scafetta.Professor of atmospheric physics at the University of Naples, Scafetta is one of Italy's climate contrarians who, due to his academic role, should have, at least on paper, the skills to deal with climate change.However, his research has a single objective:demonstrate that climate change is not caused by human activities.

Scafetta is convinced that the increase in temperature can be attributed to variations in solar activity and astronomical cycles.Regarding the first, there is no evidence that solar activity is somehow linked to current global warming.The increase in temperature shows that it does not overlap at all with possible natural factors, such as the Sun, but only with the trend of anthropogenic emissions.As for astronomical cycles, we know that periodic variations in the Earth's orbit and axis (the Milankovitch cycles) produce effects on the climate, through the triggering of the beginning and end of glacial periods, but on time scales of tens and hundreds of thousands of years.However, Scafetta also talks about other cycles, proclaiming that he has discovered cycles of "5, 9, 11, 20, 60, 115, 1000 years", he states that «by oscillating, the Sun causes equivalent cycles in the climate system.Even the Moon acts on it with its own harmonics."The site experts Climate-altering, in refuting these suppositions, and the countless errors on which they are based, they talk about «irresponsible and obstinate cyclomania».This cyclomania allows him to be interviewed, cyclically, in newspapers that have an ideological interest in proposing this type of thesis to their readers.Scafetta is one of the Italian signatories of the petition, circulated in 2019, which asserted the non-existence of the climate crisis, based on old arguments, as repetitive as they are inconsistent, such as the "CO2 It's good for plants."

We might ask ourselves:if research is so poor and if a thesis is so baseless, how is it possible that they can end up, even if in rare cases, in specialist journals?Doesn't the publication give these hypotheses some scientific dignity?Peer review and publication of studies are necessary stages of the scrutiny process through which science examines hypotheses and claims.This is what distinguishes a scientific article from an interview given to a newspaper.But it is not a perfect system, nor is it free from errors.Furthermore, beyond the rigor of the checks carried out by the reviewers (not always of excellent quality) and the quality of the various journals (which is not always equal to that of journals such as Nature And Science), the single article does not, by itself, establish the position of science on such a vast topic as climate change.The single article is a piece of a picture that is made up of a number of studies carried out by multiple scientists:it is, precisely, what we call consensus.

In 2015 a group of researchers, including the climatologist Katharine Hayhoe and I psychologist, disinformation expert, Stephan Lewandowsky, reviewed the errors and flaws present in 38 articles contesting anthropogenic global warming (articles by Scafetta also appear).A frequent feature is the omission of contextual information or data that could disprove the conclusions.Other flaws in these "skeptical" articles are the use of inappropriate statistical methods, the assumption of incorrect premises and logical fallacies such as false dichotomies.

The second study on the scientific consensus that appeared in 2021, by Krista Myers and other authors, replicated a methodology used in a work by 2009.The authors carried out a survey of scientists specializing in Earth sciences.Of all those (2548) who answered the question about the cause of global warming, 91.1% indicated human activities.By narrowing the field to experts in climate and atmospheric sciences (153), for whom it is possible to verify a high level of competence on climate change (at least 50% of their studies have this topic as their subject), the consensus rises to 98.7 %.The percentage reaches 100% if we consider the authors who published at least 20 studies on climate change between 2015 and 2019.These results demonstrate that “competence predicts consensus.”As previous studies had already shown, the data highlights that the greater the expertise, the greater the agreement on the existence and anthropogenic causes of climate change.

A topic of discussion among experts was the treatment to be applied to scientific articles that do not openly declare a position on climate change.In Cook and colleagues' 2013 study these articles comprised 66.4% of the database.It must be considered that the same scientist may have published articles in which he sometimes expressed his position through some statement and others in which he did not.In other cases the position may be implicit.This is not an anomaly, it is also found in other sectors of science.Seismologists and volcanologists do not explain in each of their studies what they think of the plate tectonics, because this theory has been an undisputed pillar of geology for decades now.Evolutionary biologists do not have to reiterate, at every opportunity, that they are convinced of the correctness of the theory of evolution and natural selection, because evolution is a cornerstone of contemporary biology ("nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution,” he saysgoes the geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky).

As we have seen, the formation of a consensus is a process that leaves traces in the scientific literature.From it we can also draw indications on what the evolution of the debate on an issue has been.In an article titled The temporal structure of scientific consensus formation, sociologists Uri Shwed e Peter Bearman they asked what trajectories debates in science take and when a scientific community reaches agreement on a fact.When and how do we become certain that smoking is a risk factor for developing cancer or that human activities are causing global warming?To answer these questions, Schwed and Bearman did not survey scientists or evaluate the content of scientific articles, but studied their citation patterns.

The conceptual starting point is the image of the black box, developed by the sociologist of science Bruno Latour:when a scientific fact consolidates its internal constituent elements are hidden;when a fact is still in the construction phase its internal elements are visible.Like a computer which, once assembled and functioning, must no longer be disassembled (unless there is a malfunction) and all of its internal components remain hidden from view, so a scientific statement, such as smoking causes cancer, is built over time within a network made up of people, studies and also elements external to the scientific community (think of everything that revolves around preventive health policies).

If we analyze the network of citations between the authors and articles of a scientific community, we recognize a structure that indicates the degree of division within the literature.A community is a network, a subset of a larger population, in which internal ties are prevalent over ties with other subsets.«We can observe the black boxing in citation networks or, more precisely, in representations of scientific articles linked by citations." When different factions debate a scientific issue, they create distinct regions within the network.The internal elements are visible, because the scientific fact is being built.

Schwed and Bearman applied this theory not only to the literature on climate change, but also to literature in other fields, such as the relationship between cancer and smoking, and to topics on which there has been no real scientific debate, such as link between vaccines and autism (a hypothesis never tried - fruit of one fraud - which the scientific community promptly denied).In the latter case the discussion follows a flat trajectory:the topic never became scientifically controversial.In the case of the relationship between smoking and cancer, the scientific debate follows a cyclical trajectory for a good part of its time span.After that, following the publication of some important studies And relationships, a first consensus on the carcinogenicity of smoking was formed between the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, the question was later reopened in different terms, as when discussions began on the possibility of manufacturing safer cigarettes and the role of nicotine.This, according to Schwed and Bearman, is also due to the influence that the tobacco industry has managed to exert on research.

The formation of scientific consensus on climate change develops along a third type of trajectory, called "spiral": an initial debate is followed by a rapid resolution of the issue and a spiral of new questions towards which the scientists' attention is directed.The reality of the phenomenon and its anthropic causes are no longer debated, but a discussion continues on other aspects of the issue.Schwed and Bearman looked at 9423 scientific articles on climate published between 1975 and 2008, finding that by the early 1990s the consensus had become consolidated.

Can this consensus be overturned?In principle yes, if new and convincing evidence becomes available.But the level of consensus also tells us what the state of the discussion is in the scientific community.It is a measure of any dissent within it and therefore, indirectly, of the plausibility of alternative hypotheses, put to the test of scrutiny by the scientific community.If consensus on anthropogenic climate change is close to 100%, this means that there is no debate about its reality among the most competent scientists.

Naomi Oreskes he states that «most people think that science is reliable by virtue of its method:the scientific method".But there is no single scientific method.What makes scientific statements reliable is, according to Oreskes, «the process by which they are verified.Scientific statements are subject to checks and only those statements that pass them can be said to constitute scientific knowledge."

In the case of climate change this process of scientific control has long come to an end.Science today is certain that it is caused by emissions produced by human activities (primarily, by the use of fossil fuels), just as it is certain that smoking is carcinogenic.Anyone is free to believe that those who improperly call themselves "skeptics" are right and that the scientific community is wrong.Personal opinions are free.What one cannot do is claim that the scientific community is split and that scientists are still debating the reality and causes of climate change.Because these, as studies show, are false statements.

Preview image via psmag.com