https://www.valigiablu.it/ricchi-tasse-pagare-crisi-climatica-impatto/

- |

Science has demonstrated, beyond any reasonable doubt, the anthropogenic impact on global temperature increases.According to the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the temperature increase from 1850-1900 due to human activity is valued at around 1.1 degrees centigrade and that, even with rapid and large-scale interventions, it will take at least thirty years before the climate stabilizes.

The question then shifts to the type of policies and behavioral changes necessary to reach climate targets and limit the temperature increase to between 1.5 and 2 °C by the end of the century, the limit threshold set by the Agreement reached at the Conference of United Nations Climate Change Report of 2015 and, beyond which, potentially irreversible turning points could be overcome, as shown in a report by the IPCC of 2018.To do this it is necessary to consider three aspects.

The first is still the scientific one, monitoring the dynamics of climate phenomena and anomalies together with the emissions trend.

The second is the economic aspect.What policies are to be adopted?There are two objectives to be reconciled, the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and the mitigation as much as possible of the repercussions of these policies on people's well-being and their standard of living.This is a topic that economists have long debated.Initially the economic community provided a worrying response:the DICE model formulated by Nobel Prize winning economist William Nordhaus he esteemed in fact, the optimal temperature increase to avoid repercussions on economic growth should have been 3.5°C by 2100, well above scientists' recommendations.

The most recent studies show instead, how it is possible to combine economic growth and combating the climate emergency.In a study conducted, among others, by economists Daron Acemoglu and Philippe Aghion - among the leading experts in Growth Theory - the authors they notice how an ecological transition requires temporary investments that incentivize cleaner technologies and sectors, together with a carbon tax.Furthermore, time plays a central role:Delays in implementing policies to combat the climate emergency can be extremely costly.

However, there is a third aspect to consider.Precisely because policies and the climate crisis affect the well-being of individuals and cascade on the consensus of politicians, it is necessary to also take this last aspect into consideration if we want to build a strategy to combat the climate emergency that is not only effective, but also fair. , assuming that without equity there can be a transition.It then becomes particularly important to understand the mutual interaction between them policy and the climate transition have a profound impact on a population heterogeneous, which includes an extremely rich minority on one side and the remainder (the middle class and the less well-off) on the other.

What we talk about in this article:

The majority of people pay for the pollution of the rich

Often the political-social response is invoked by politicians and agenda setter right-wing to oppose any attempt to combat the climate emergency.Over the years, even leading political figures they spoke of the so-called "ecological madness" of Brussels and how they would only make people's lives worse.A closer look, guided by scientific rigor, shows that it is ordinary people, not the super rich, who are damaged by the climate emergency.

Particularly on a theoretical level, a work by the Department of Economics and Social Affairs of the United Nations has identified three channels through which the climate crisis would have a greater impact on ordinary people and the less well-off.

The first concerns the location of homes.People with fewer financial resources tend to reside in more vulnerable areas, such as near rivers subject to frequent flooding or on land characterized by high hydrogeological risk.This increased exposure is not random, but is the result of a series of economic and social circumstances that force poorer people to live in less safe areas.This exposes them more to the damage caused by extreme climatic events, causing greater losses than those who live in less dangerous areas.

The second mechanism concerns the fragility of these homes in the face of extreme climate events.The homes of people with fewer economic resources are often built with less resistant materials and with lower safety standards than the homes of wealthy people.Therefore, in the event of hurricanes, earthquakes or other natural disasters, the homes of the poorest tend to suffer much more serious damage.This increased vulnerability not only puts the lives of the inhabitants at risk, but also entails high costs for repairs and reconstructions, further worsening the already precarious economic situation.

The third mechanism focuses on the ability to recover from the consequences of extreme climate events.Economically advantaged people have greater financial resources and access to insurance and credit tools that allow them to better deal with the damage and losses they suffer.They can then rebuild and recover more quickly.In contrast, the less well-off, with limited resources, find it enormously difficult to recover after a disaster.The lack of funds, social support and access to credit often forces them to live in worse conditions than before the event.This cycle of vulnerability and difficulty in recovery contributes to perpetuating and worsening economic inequalities, creating a negative spiral from which it is difficult to escape.

But there are not only direct impacts.Extreme climate events would damage the harvest, increasing the price of fruit and vegetables and thus affecting low-income families.Just as hot summers could influence the use of refrigeration systems, eroding the income of even average families.

Several studies have confirmed these hypotheses.A 2015 study has analyzed data relating to the city of Mumbai, India, demonstrating how floods damage the poorest citizens the most and underlining how the situation is destined to worsen without adequate government support.Another study conducted by a group of Italian researchers in 2022 reached similar conclusions.Increased rainfall in countries with an economy heavily based on agriculture has had a greater negative impact on the poorest segments of the population.According to these researchers, an increase in the weight of the industry in the national economy could reduce the impact of extreme climate events.

But the industrial sector itself and the transformations it will have to undergo show another aspect, this time more economic, of the vulnerability of working groups to the climate crisis.An example comes from sectors in which it is difficult to reduce the amount of polluting emissions.

An example above all is the steel industry.The sector has seen its emissions stay stable over the last few years, after an increase in previous decades due to growing demand: it is estimated that between 8 and 10% of emissions come from this sector globally.It is likely that not all companies will have the investment funds necessary for steel production cleaner.This will lead to the closure of the companies themselves which will end up out of the market due to regulations or high costs.This is not in itself a problem, given the process of "creative destruction" that drives the economy.The risk falls above all on workers, who in the sector are often in an advanced age group and without tertiary education.Their transition to another job can be extremely complicated.

Still remaining on the relationship between policies and inequalities, but also considering the reverse effect, it is necessary to cite a work by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which consider the impact from the point of view of the consensus of governments committed to combating the climate crisis.The researchers estimate that these are politically costly measures:they usually cause the government that implements them to lose consensus.But, they underline, the result appears different based on the type of measures implemented.

As we had already written in a previous article, policies to combat the climate emergency in the economic field can be divided into two categories:type policies market based, which act on prices and incentives;type policies command and control, That they intervene instead on quantities through regulation and are usually accompanied by industrial policy investments.They are the first to be more expensive from a political point of view.In fact, since the middle and low income classes dedicate a greater portion of their income to consumption, taxes that incentivize certain behaviors (for example the increase in fuel prices) tend to have a regressive effect and therefore weigh more.This does not mean that, even in this case, the implementation of the policy is of fundamental importance:a carbon tax like that of British Columbia - which has unchanged revenue going to finance a tax cut - is an example of political market based effective.

How the elite impacts the climate crisis

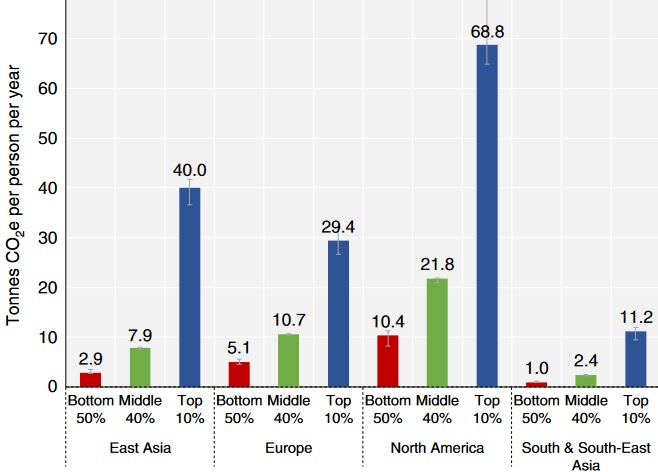

In a work published on Nature by Lucas Chancel, economist at the Paris School of Economics, was calculated the impact, by macro geographical area, of emissions based on income bracket.As can be seen from the Figure 1 the differences by income bracket - Bottom 50%, Middle 40%, Top 10% - show a trend growing in each macro area considered.In Europe, the average level of tonnes of CO2 equivalent of Bottom 50% is six times lower than the Top 10%, while in North America the gap is even greater.Even globally, yes law in the World Inequality Forum report, there has been an increase in the growth of emissions in developing countries since the 1990s, but also a dramatic increase in the global top 1%, responsible for a quarter of this growth.Meanwhile, the middle and lower classes in developed countries have seen a decline in emissions.

However, it is important to note how the elite and even part of the middle class in advanced countries have a greater impact on emissions.The first channel is consumption.For example, wealthier people use more expensive, but also more polluting cars such as SUVs.According to statistics, without an adoption of SUVs like status symbol, emissions from motor transport they would be could have fallen by 30% more from 2010 to 2022.

The same can be said for air transport, which is a significant component of emissions globally, especially when talking about long journeys.British data show as the emissions of the richest groups linked to air transport are higher than the emissions caused by the poorest groups in every aspect of their existence.A topic that has attracted the attention of public opinion, linked in particular to the use made by celebrities such as Taylor Swift or Elon Musk, is that of jets.According to a report by the European Federation for Transport and the Environment, the use of jets turns out between 5 and 14 times more polluting than a commercial plane per passenger and 50 times more polluting than trains.Also according to the report, some of these jets emit two tons of CO2 At that time:for comparison, the average annual impact per capita is estimated to be 8.2 tonnes in advanced economies.

But it's not just consumption:as an article on explains The Conversation, the problem is that the economic elite owns polluting industries or invests in them, at the same time controlling media and making lobbying so that regulatory policies are less stringent.In particular, it is often the same managers of the polluting companies who do hold shares of their companies which are incentivized to “business as usual” compared to the investments necessary for the economic transition.

As it has underlined one of the scientists who contributed to the Paris Agreement, Laurence Tubiana, the time has come for the polluting elite to pay to finance the ecological transition that it is instead hindering.There are various proposals on this topic, starting with specific taxes for example on first class flights, so as not to affect the middle and lower classes.But the most ambitious proposal comes from a progressive tax applied either globally or through cooperation between states.

This is in fact what the aforementioned Chancel and the French economist Thomas Piketty propose in one of their articles.For Piketty and Chancel, people who emit a quantity of CO2 above a certain threshold value should contribute to a global fund for climate adaptation.Ideally, this carbon tax would be applied globally, but the authors themselves acknowledge that such an implementation is far-fetched.The alternative is for each country to contribute to the global fund based on what the global progressive tax would calculate.Individual countries could then decide how to raise the funds, for example through their own progressive carbon tax.The authors then suggest that countries could also use an income tax surcharge for major emitters, with marginal rates varying depending on the level of emissions.

The overall goal, therefore, is that richer countries, which have historically contributed the most to CO emissions2, provide the majority of funding for climate adaptation.

But this must also pass through a review of general taxation to finance those redistributive policies that will be necessary for the climate transition.An example was recently provided through a simulation of how energy production would change in Italy.The installation of photovoltaic panels and therefore solar energy will play a crucial role in our country.But the necessary investments, underline the researchers of the Grins foundation, could damage the less well-off sections of the population, through energy prices.This does not mean, as is made to believe on the right, that we should not proceed with the climate transition, but that this must be accompanied by redistribution measures to protect the affected groups and prevent this from having repercussions on the consensus of the governments in office.

The transition must not only be ecological, but also just

The costs of the transition and the repercussions on the weakest groups are often cited as a reason to proceed with caution at the legislative level.From what we have seen, however, it is the climate emergency itself that weighs more heavily on these bands, where however the margins of control are more limited.For this reason, in order for the ecological transition to have the support of the majority of people, it is necessary to take into account the heterogeneous effects that policies and climate emergencies have on the population, in particular as income and wealth vary.

Only by taking these aspects into consideration, is it possible to implement policies that have no impact on the electoral consensus of governments, thus discouraging the fight against the climate emergency.This involves in particular understanding how the polluting elite is the most responsible, through the various channels we have seen previously, for the climate emergency.Intervening decisively with regulation and taxation on these aspects would have an impact on the growth of emissions on the one hand, and on the other the possibility of financing adaptation funds to the climate emergency and the necessary redistributive policies.

The risk, as already mentioned, is that the effects of lobbying and a policy that increasingly benefits the wealthy sections of the population put this program at risk, with worrying effects on the evolution of the climate emergency.

Preview image via Peace Science Digest